Geology

‘Digging deeper’ – what geology tell us about the Broads landscape

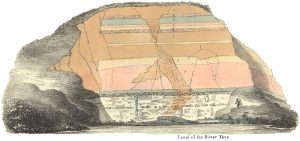

The fens, meres and marshes of the Broads rest on thick layers of peat and silty clay – the one formed in freshwater swamps and the other in estuarine conditions. These layers have been building up since the end of the last ice age.

The Broads lies so close to sea level that its shallow valleys are at the mercy of the North Sea. The coast has advanced and retreated across the area for millions of years, and the layers of sediment infilling the valleys are just the latest deposits in that story.

Jumping back in time 20,000 years, the Broads was a chill landscape gripped by the last ice age. There would have been no trees, only hardy, dwarf bushes and lichens grazed by wild horse and reindeer in summer time.

The ancient rivers Bure, Yare and Waveney flowed at levels deep beneath present valley bottoms, and drained out into a vast plain we call Doggerland, where the North Sea now lies. Seasonal snowmelt would have turned these rivers into meltwater torrents, as seen today in northern Canada and Siberia. The Broads was just an upland area on the western side of the plain.

At least two major ice sheets have left their mark on the Broads area. The one (the ‘Happisburgh’) swept down from the north, perhaps 600,000 years ago. The second one (the ‘Lowestoft’) advanced from the north-west about 450,000 years ago. They left a jumble of glacial clays, sands and gravels that now form the gently undulating uplands that frame the Broads landscape.

The sands and gravels have been quarried for aggregate at Aldeby, Haddiscoe, Burgh Castle and Whitlingham. The clays have been dug for brickearth, as at Somerleyton brick pits.

Two million years ago the Broads area was covered by the North Sea. We know this because the sandy deposits that outcrop along valley sides at places such as Strumpshaw and Bramerton could only have been laid down in marine conditions.

Known as the ‘Crag’, they contain fossil sea shells and occasionally the remains of land animals washed out to sea. There are also muddy deposits, most likely to have been laid down in estuaries or tidal flats, as seen in The Wash today.

Chalk bedrock underlies the Broads area. It is close to the surface near Norwich and Wroxham, where the river valleys of the Yare and Bure have cut down to meet it. To the east, it is far too deep to reach, lying over 150 m (492 ft) down beneath Great Yarmouth.

Chalk used to be dug by hand from quarries on the valley sides, then transported by wherry to kilns where it was turned into builder’s lime, as at Ludham. It was also used for agricultural lime to improve the fertility of sandy soils. Flints from the chalk were a handy and valuable source of building stone.

‘Stony rubble’ – geological stories in old walls

The Broads area lies at the crossroads of all sorts of geological influences. Local fields are scattered with many interesting stones; most are flint, but a surprising number were brought from far away by ice sheets or now-vanished rivers.

Many of the larger stones were collected from local fields and used for building walls. This geology is an interesting part of the architectural story of Broads churches.

There is a shortage of building stone in the Broads. Flint is abundant but, unless the nodules are unusually large, it can only be used to build flat walls or circular towers. Flint courses need to be framed by blocks of ‘ashlar’ stone to form keys and quoins (corners). Blocks of sandstone and limestone were imported in Mediaeval times for this purpose. The chief source was from the other side of the Fens, in the Stamford and Peterborough area where honey-coloured Jurassic stone was quarried and shipped out by boat. It could also be used for framing flint panels and for the structural details of windows and doorways.

Flint is abundant in the Broads area and is used in various ways, including raw nodules, split (knapped) pieces and rounded, water-worn cobbles. It comes from the glacial deposits of the upland areas flanking the valleys, and from local beaches. It tends to be light grey in colour here, in contrast to flint from other parts of East Anglia which tends to be dark grey, sometimes with a brownish tinge. Some flints are orange stained, which suggests they have spent time in iron-rich gravels.

Cobbles of pink, grey, white and brown quartzite are often found in old walls. Quartzite is a very hard kind of sandstone where the sand grains have been cemented by silica or even partly fused together by pressure. These quartzites originated in the Triassic rocks of the Midlands, and were eroded then brought to the area by now-vanished rivers, perhaps a million years ago.

Ship’s ballast was a handy source of building stone. In Mediaeval times, the Broads area had important overseas trading links. Ships criss-crossed the North Sea with export goods, for example Norfolk wool, and were ballasted with boulders to keep them steady on the return journey. These rocks could then be sold as useful building material.

The Broads area is overlooked by sandy and clayey uplands such as Lothingland and the Isle of Flegg. They are founded on glacial sediments, some of which are suitable for making bricks; they are typically red or pale buff in colour and filled with grit and small pebbles.

By contrast, the valley floors are often underlain by layers of clayey alluvium formed in estuary or saltmarsh. This finer material may be suitable for making stoneless bricks, which come in a variety of colours. Some have a bubbly-looking black interior, caused by firing organic-rich inclusions in the clay.

‘A load of old ballast’ – odd rocks from overseas lurking in our walls

The old stone walls of the Broads are a treasure trove of interesting rock types. Most of them are locally sourced material, such as flint, limestone and quartzite, but there are also a surprising number of exotics from distant places.

There are rocks from upland Britain, such as dolerite from Teesdale in County Durham, which were brought to the area in the bedload of ice sheets. It is difficult to tell them apart from ones that arrived as ship’s ballast.

In Mediaeval times, the Broads area had important trading links with north-west Europe. Ships criss-crossed the North Sea with goods, for example Norfolk wool, and were sometimes ballasted with boulders to help keep them steady. If a ship came from the Baltic, for example, it might be ballasted with Scandinavian rocks from a local beach, which were offloaded when it got to England and took on cargo.

In 1345 a captain was fined 6s 8d at Great Yarmouth for ‘casting his ballast into the haven’. A much better idea was to sell it by the cartload to church builders.

There are distinctive pieces of dark grey volcanic lava in the walls of many Broads churches. These are fragments of circular quern stone used from milling corn, and were imported in Mediaeval times from quarries at Niedermendig and Mayen in the Rhineland. Typically, the dressed upper surface is worn flat by grinding. Sometimes a segment of the broken circle can be seen, which allows us to estimate the diameter of the original.